|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VARIEZE

Model 28 Mini-Viggen

Model

31 VariEze POC

Model 33 VariEze

Air Sport EZ (VariEze O-235)

Ganzer Gemini

![]()

LONG-EZ

Model

61 Long-EZ

Model 61-B Long-EZ-B

Long-EZ-160

Perry Mick's Duckt![]()

TWIN-ENGINED VARIANTS

Ivan Shaw's Twin-EZ

Michael Bowden's Two

EZ MS1![]()

MILITARY VARIANTS

Sneeky

Pete

Monkey

Green / Vz-10

California Microwave/Lockheed CM-30

Model 144 CM-44; CM-46

N.A.L. LCRA

DRDO-ADE Rustom-I![]()

JET VARIANTS

Jet LEZ Vantage (Task Vantage)

XCOR Aerospace EZ-Rocket

AFRL/ISSI Borealis (Long-EZ PDE)

COZY

Puffer/Co-Z Cozy Classic/RG

Puffer/Co-Z Cozy Mark III/RG

Puffer/Co-Z Cozy Mark IV/RG

Dickey E-Racer Mk-1

Richter CozyJet

Aeromet AURA

Leon Twin

Cozy, Xtra EZ![]()

VELOCITY

Velocity 173, Velocity Elite

Velocity

SE, Velocity SE RG

Velocity

XL, Velocity XL RG, Velocity XL-5

U.S. Army Vz-11

Others: VJet 900, X-Racer, V-Twin![]()

BERKUT

Berkut 360, Berkut 360 FG,

Berkut 540, Berkut 540 FG

Super Berkut

540

Berkut Jet, Dick Rutan's Berkut![]()

PROXY

SkyWatcher, Firefly, SkyRaider![]()

OTHER EZ-INSPIRED DESIGNS

Wright Stagger

EZ

Beard Two-Easy

Glassic SQ2000, Conner Rotor-EZ

Parrish Dart

Heier Gemini

ADS A-701 Dominator UAV

Infinity 1, CH-3 UAV,

Griffon/Mobius, Stag-EZ,

Open-EZ, Phoenix, Orion GT,

AeroCanard, Speed Canard

Haynes Skyblazer

VARIVIGGEN

Model 27 Vari-Viggen

Model

32 Vari-Viggen SP

Chasles Microstar

Rayne Viggenite, Olson Viggenite 13B ![]() DEFIANT

DEFIANT

Model

40 Defiant POC

Model 74 Defiant ![]() QUICKIE

QUICKIE

Model

49 > Model 54 Quickie

Quickie Q2, Q200

Tri-Q, Super

Quickie

Dragonfly Mk.I

Dragonfly Mk.II/H

Dragonfly Mk.III

Eagle X-P1, Eagle X-TS 150

Big Bird (Free Enterprise)

![]() SOLITAIRE

SOLITAIRE

Model 77 Solitaire

Task Silhouette

Harrison Skyblazer

R.A.F. SINGLE-PROP ONE-OFFS

Model 68 Laser (AmsOil Biplane Racer)

Model 72 Grizzly

Model 76 Voyager

Model 81 Catbird

Model 97 Microlight > Mercury

Models 58/59 > Model 120 Predator![]() SCALED SINGLE-PROP AIRCRAFT

SCALED SINGLE-PROP AIRCRAFT

Toyota Lima 1 (modified Piper Aztec)

Model 191 Toyota Lima 2

Model 302 Toyota TAA-1 Budgie ![]()

Model 309 Twin Recip (Adam 309)

Adam A500 CarbonAero

Adam A700

DARPA Heliplane![]()

Model 355 Firebird > production version

Model 367 BiPod

Bird Symmetry![]()

MULTI-PROP AIRCRAFT

Model

78/79 Commuter

"21st Century Aircraft"

Model 115 NGBA (Starship-1)

Beechcraft Model 2000/A Starship

Model 133

SMUT (ATTT)

Model

158 Pond Racer

Models 209-220 TIDDS (SOFTA)

Model 254 Songbird

Model

202 Boomerang

Morrow MB-300 Boomerang

Model 356 Johnson Dynamite

Model 35

Ames AD-1 'Skew Wing'

![]() MILITARY JETS

MILITARY JETS

Model 73 NGT > Fairchild T-46

Model

151 ARES (LATS)

Tailsitter Stealth Fighter

Models 208, 215, 222 TIDDS (SOFTA)

Model 223 TIDDS (SOFTA)

Manta

![]()

BUSINESS JETS

Model

143 Triumph ("Tuna")

Model

247 Vantage (Visionaire VA-10/A)

Eviation EV-20A Twin Vantage

Model

271 Williams V-Jet II

Model

301 Pronto > Eclipse 500![]() HIGH FLYERS

HIGH FLYERS

Grasshopper (CLA)

Model

281 Proteus, Model 395

Model

311 Capricorn (GlobalFlyer)

Model

318 White Knight

Singapore Aerospace LALEE

LLNL Defender

Model 348 White Knight Two

Model 351 Stratolaunch Roc VLA

Model 226 Raptor/Talon (Quiver)*

Model 233 Freewing (Scorpion)

BAE Systems unnamed target![]()

Model 281 Proteus*

Singapore Aerospace LALEE*

LLNL Defender![]()

TRA 410 Affordable UAV*

TRA 324 Scarab > Scarab-LACM

TRA 350 Peregrine (BQM-145A)![]() Orbital Sciences Tier II+

Orbital Sciences Tier II+

Model 260 Northrop Tier II+

Model 326 NG X-47A Pegasus

Northrop Grumman X -47B

Model 355 Firebird* > NG Firebird*

NG Proteus 'Hunter-Killer'

NG Global Hawk 'Hunter-Killer'

![]()

Bell Textron TR911X Eagle Eye POC

Bell Textron TR916 Eagle Eye (USCG)

Bell Textron TR918 Eagle Eye

![]() IAI-Malat Scout > Searcher/Chugla

IAI-Malat Scout > Searcher/Chugla

![]()

Aeromet AURA*

California Microwave/Lockheed CM-30*

California Microwave CM-44 (Model 144)*

California Microwave CM-46*

ADS A-701 Dominator

CH-3 (China)![]() * indicates optionally-piloted vehicles

* indicates optionally-piloted vehicles

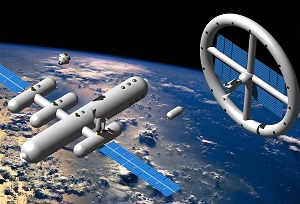

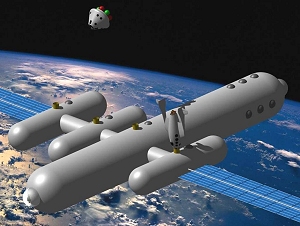

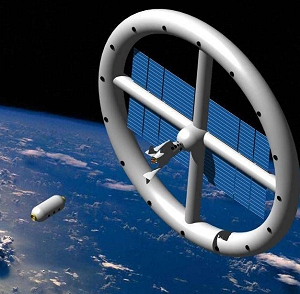

SINGLE-STAGE TO ORBIT

Pacific American Phoenix-M

Clapp/Rutan/Raymer Black Horse

McDonnell Douglas DC-X Delta Clipper

Rotary Rocket Roton

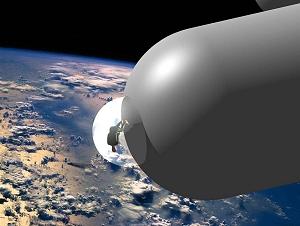

![]() SPACESHIP EVOLUTION

SPACESHIP EVOLUTION

Faget/Johnson Maliboo

SpaceShipOne scale

models

Model 316 SpaceShipOne

Model

346 SpaceShipTwo (project)

Model 339 SpaceShipTwo

Models 340-344 Space Resort

![]()

OTHERS

Kistler

Zero (K-0) TSTO

Darpa/SLC RASCAL TSTO

Crew

Transfer Vehicle (CXV)

Comet/Meteor module (CSTAR)

Model 267 NASA X-38A (CRV)

CAPSULES/GONDOLAS

PLADS/Rockbox

Earthwinds Hilton

Voyager Aeolus 1

WF-1 Global Hilton > Voyager 6 DLS

Virgin gondola ![]()

AIRCRAFT PARTS

Bölkow Junior canopy

Tacit Blue composite elements

Senior Citizen (unknown)

Zivko EDGE wing

IAI Chugla/Searcher wing

OSC LT-11 Pegasus flying surfaces

SOFIA aperture (cavity door)

Liberty XL-2 construction > Europa

GippsAero GA8 Airvan testing

Cessna Citation composite work

Richey VersiPlane fuselage

Composite oxydizer tanks![]()

R/C MODELS

Model 1 "A-12"

Model

287 Alliance

Flight of the Phoenix flying model

Super

STOL (SSTOL) model

Model 313 scale model

Model 316 SpaceShipOne scale

models![]()

OTHERS

Northrop B-2 RCS Model

Model 173 TFV towed

vehicle

Sandia

SU-25 ROAR scale decoy

Whispercraft movie mock-up

BOATS

Ames Industrial PARLC

Sail America Stars & Stripes wing-sails

![]()

CARS

General Motors Ultralite

Clarinval Supersport S22 (S-2000)

Cal Poly Solar Car

Arizona Solar Racing Team Monsoon

Turbulence

![]()

VARIOUS

Zond Z-40 Bladerunner blades

Computer numerical control

Boeing wind tunnel

blades

Truck-based wind tunnel

Portable pedal power

Composite bridge

Overbalance water wheel

Solar water heater; Pyramid house

EZ REFERENCE